Valuation Makes The Headlines – Liquidation Preferences Allocate The Cash

Why do some startups, despite raising over $100 million and achieving unicorn status, end up with little to show for it?

The startup press and many founders are obsessed with valuation. But that can be a trap.

During a liquidation event, the most important factor is how the cash is distributed. This distribution order is known as the cap table waterfall.

If you think your waterfall is calculated based on the ownership percentage of the stockholders on your cap table, think again. Let's dig into the topic of liquidation preferences.

Liquidation events

Let's start with defining a liquidation event. Here is a fairly standard definition of a liquidation event from an investment term sheet:

A sale of all or substantially all of the assets of the Company and a merger, reorganization, or other transaction in which 50% of the outstanding voting power of the Company is transferred will be treated as a liquidation event.

For our discussion, we'll focus on scenarios in which we trigger a liquidation event by selling our startup for cash.

The liquidation preference

A liquidation preference has three essential components.

First, the preferred investor has the right to receive a multiple of their original investment before common stockholders.

Second, participation rights allow the preferred investor to receive additional cash after their liquidation preference. Participation rights can be capped or uncapped, impacting how much cash remains for the founder and their team.

Finally, preferred stock has a conversion feature, which allows the preferred investor to convert their shares to common stock if that produces a better outcome.

Let's see how this works with some simple examples.

Common facts for our examples

We will use a simple fact pattern for our four examples below.

Total amount raised: $100 million

Preferred Stockholder Ownership: 75%

Common Stockholder Ownership: 25%

Example 1

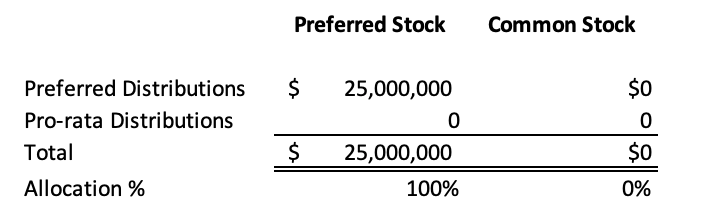

Sale Price: $25,000,000

Liquidation Preference: 1x

In this example, the preferred stock has a 1x liquidation preference. Investors are entitled to 1x their investment before any other distributions to stockholders. Since their investment was $100 million, the entire $25 million is distributed to the preferred investors.

There is nothing left to allocate to the common stock.

Liquidation preferences protect preferred investors in downside scenarios.

Example 2

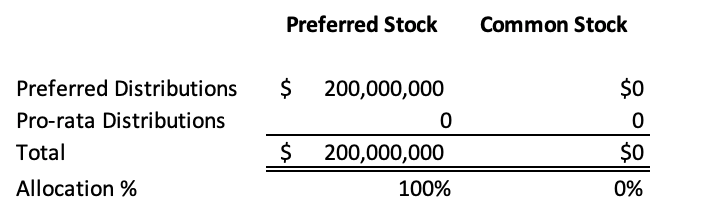

Sale Price: $200,000,000

Liquidation Preference: 2x

The 2x liquidation preference in this example means that investors get 2x their preferred investment of $100 million before any other distributions. The startup sold for $200 million, but the founders and employees will get nothing.

Now, let's introduce the concept of participation rights.

Example 3

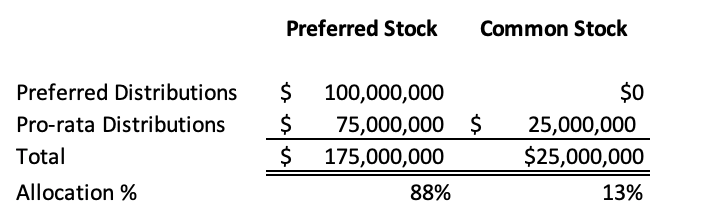

Sale Price: $200,000,000

Liquidation Preference: 1x

Participation Rights: Yes

Participation Cap: 2x

Most preferred shares are 'participating preferred.' Participating preferred shares continue to receive pro-rata distributions alongside the common stockholders after the liquidation preference.

Participation rights should be capped, limiting the total cash preferred shareholders receive. However, we'll see a way around this limitation in the next example.

The waterfall starts by distributing the liquidation preference to the preferred investors, which accounts for the first $100 million.

Since these preferred shares have participation rights, the remaining $100 million is allocated pro rata based on the ownership percentages on your cap table. Your preferred stockholders take an additional $75 million, giving them a total of $175 million. They receive 88% of the distributed cash even though they only own 75% of the startup.

You'll also note that the preferred investors receive less than 2x their original investment, so the 2x participation cap doesn't apply in this example.

Let's look at one more example, and we'll see what happens when the participation cap is a factor.

Example 4

Sale Price: $500,000,000

Liquidation Preference: 1x

Participation Rights: Yes

Participation Cap: 2x

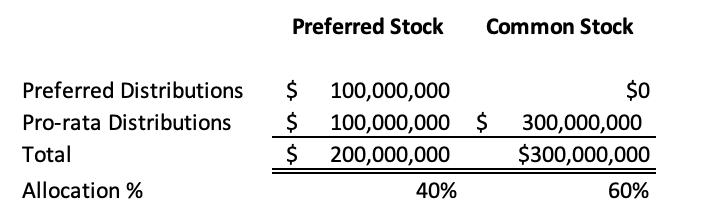

As in the prior example, the waterfall starts by distributing the first $100 million to the preferred stockholders, reflecting their 1x liquidation preference.

Because these preferred shares have participation rights, the preferred stockholders then participate in the distribution of the remaining cash, pro rata, alongside the common stockholders.

However, the participation right has a 2x cap, which means that the preferred investors can't receive more than 2x their original investment, or in this case, $200 million. The remaining $300 million is distributed to the common stockholders.

The common stockholders end up with 60% of the proceeds, even though they only own 25% of the startup. An excellent result!

NOT SO FAST!

This would be a terrific result for the common stockholders. But we're missing one last feature of preferred stock that eliminates the risk of this outcome for preferred investors.

The preferred stock conversion

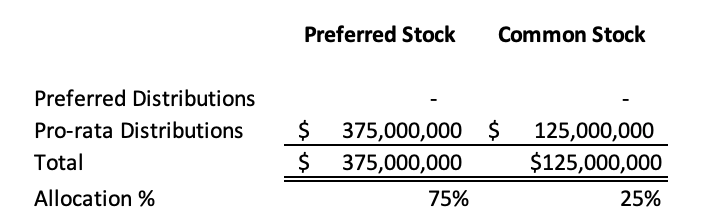

Preferred stock has a conversion feature that allows the preferred stockholder to convert their shares to common stock. Converting from preferred to common stock makes sense when the startup has an extraordinary outcome, and the preferred stock has a participation cap.

How do you get around a participation cap? Convert the preferred stock to common stock. This move eliminates the participation cap and allows preferred stockholders to participate in the waterfall pro rata from the first dollar.

In the above example, the preferred stockholders would convert to common stock and be entitled to 75% of the proceeds rather than the 40% allocated to their preferred stock.

This results in the preferred stockholders receiving $375 million rather than being capped at $200 million.

Liquidation preferences protect preferred investors in downside scenarios. If a company has a great exit, preferred investors can convert their stock to common shares and participate in the liquidation event pro rata.

The preferred investor can choose the option that produces the best outcome for their fund.

Preference Stacks and Waterfalls

I've tried to make these examples as simple as possible to highlight the basic concepts. In practice, this can all get very complicated, particularly as you raise multiple rounds of financing.

The liquidation preference and participation rights are specific to each series of preferred stock. In other words, it's possible, and quite common, for various series of preferred stock to have different liquidation preferences and participation rights. The term "preference stack" refers to the layers of liquidation preferences that are a part of your cap table after successive rounds of funding.

The calculation of the cash distribution waterfall becomes more complex as you have a growing preference stack, requiring you to move from layer to layer to distribute a shrinking pile of cash.

Later-stage investors can use preferences to give them a distribution advantage over earlier preferred stockholders, pushing common stockholders further down the preference stack.

Don't trade valuation for structure

Did you notice that we didn't discuss valuation? Valuation is about ownership. Ownership matters if you have a great outcome and the cash is distributed pro rata.

Structure on your cap table, such as liquidation preferences and other preferred investor-friendly provisions, raises the hurdle your startup must overcome to deliver meaningful value to you and your team.

Whether you're simply trying to bump up your valuation or your startup is running out of cash, trading valuation for structure can dramatically limit your potential future outcomes.

Do the math. Understand your cap table's waterfall. Valuation makes the headlines. Liquidation preferences allocate the cash.

Dig Deeper

🗣️ Leave a comment or question below

📫 Email me at eric@startuproadmap.com

🖥️ You can learn more about working with me here

📚 Check out our growing resources section